ADVERTISE HERE

AS Ramadan unfolds, many Muslims living with diabetes are navigating a deeply personal decision each day. Fasting is not simply a change in meal timing. It is a metabolic shift that influences blood sugar control, medication timing, hydration, and overall energy balance.

AS Ramadan unfolds, many Muslims living with diabetes are navigating a deeply personal decision each day. Fasting is not simply a change in meal timing. It is a metabolic shift that influences blood sugar control, medication timing, hydration, and overall energy balance.

The National Health Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2023 reports that 15.6% of Malaysian adults have known diabetes, while international estimates from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) suggest that total diabetes prevalence including undiagnosed cases may exceed 21%. This distinction highlights the large proportion of individuals who remain unaware of their condition. These numbers reflect a continuing and serious public health challenge.

Ramadan introduces specific risks. The IDF in collaboration with the Diabetes and Ramadan International Alliance (DAR) estimates that globally more than 150 million Muslims with diabetes fast during Ramadan each year. Evidence from large observational studies such as the EPIDIAR study has shown that the incidence of severe hypoglycaemia may increase several folds during Ramadan among high-risk individuals, particularly those treated with insulin or sulfonylureas.

In Malaysia, clinical management of diabetes is guided by the Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH). These guidelines emphasise individualised care, medication adjustment and structured education. Patients with recurrent hypoglycaemia, poor glycaemic control, advanced chronic kidney disease (stage 4 or 5), pregnancy with diabetes, or acute illness such as infection, fever, and recent hospitalisation are categorised as high risk and are generally advised not to fast. International guidelines also emphasise that patients in the very high-risk category are strongly advised not to fast due to the likelihood of severe complications. This risk-based approach aligns with Islamic jurisprudence, which permits exemption from fasting when health is threatened.

The physiological risks during Ramadan are predictable. Hypoglycaemia or low blood sugar often occurs in the late afternoon after prolonged fasting, especially in patients taking insulin or insulin secretagogues. Symptoms such as sweating, trembling, confusion and palpitations must not be ignored. Severe hypoglycaemia can lead to seizures or coma. Hyperglycaemia is equally concerning. Large iftar meals rich in refined carbohydrates and sweetened drinks can produce rapid glucose spikes. Repeated hyperglycaemia contributes to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and in severe cases may lead to severe dehydration and dangerous complications. In insulin deficient individuals, there is also risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) if insulin doses are omitted or significantly reduced.

The MOH recommends pre-Ramadan assessment ideally 1-2 months before Ramadan. This includes reviewing HbA1c levels, which reflect long term blood sugar control, kidney function and current medication regimens. Medication timing is often adjusted rather than stopped. Medication timing is individualised, with some once daily agents often shifted to iftar under medical supervision.

Medication management during Ramadan must never be improvised. The MOH emphasises individualised adjustment rather than omission of therapy. In general, medications with low risk of hypoglycaemia such as Metformin are often continued, with doses divided between iftar and sahur depending on the regimen. Some older diabetes tablets carry a higher risk of low blood sugar and may need dose adjustment.

Some newer diabetes medications carry lower risk of low blood sugar but may still require caution, especially in hot climates where dehydration is a concern. Insulin regimens often need modification, commonly involving reduction of daytime doses and careful monitoring in the late afternoon. The IDF DAR guidelines stress that patients should never stop insulin abruptly and should not independently alter doses without professional advice. The principle is adjustment, not abandonment.

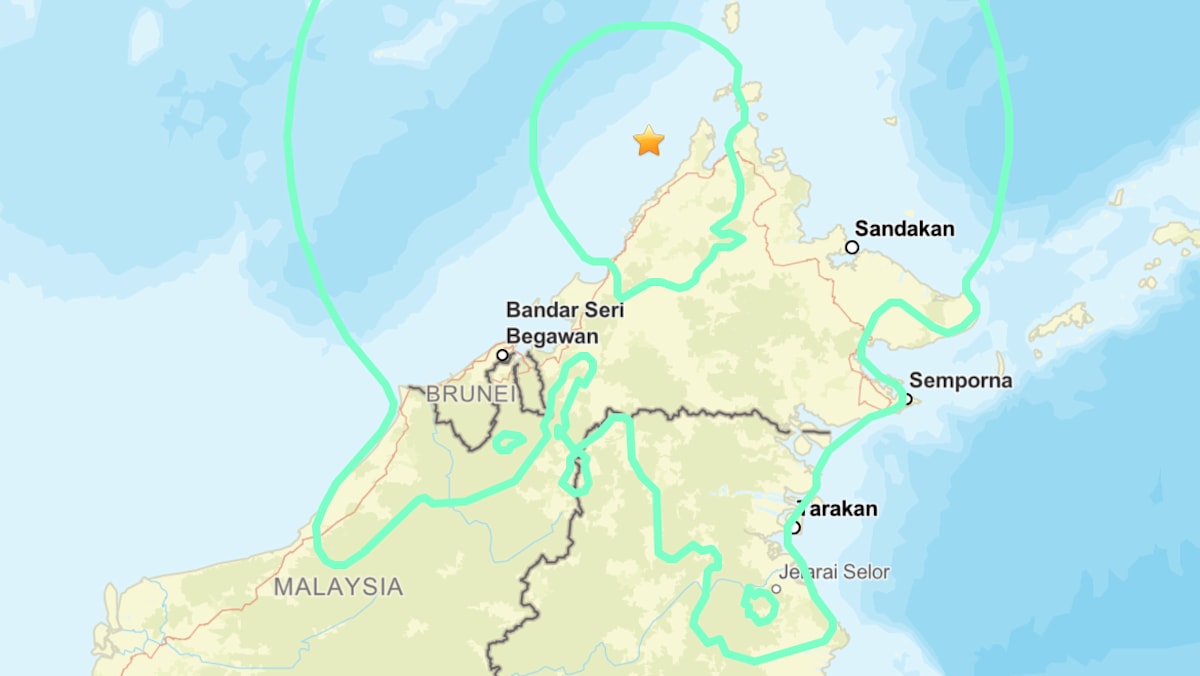

In Sabah, geographic distance and healthcare access barriers may make timely pre-Ramadan review more difficult for some patients, increasing the importance of proactive follow-up. A common scenario in primary care involves patients who decide independently to reduce insulin doses out of fear of hypoglycaemia, only to present later with persistently high glucose readings. These preventable destabilisations often stem not from religious devotion but from lack of structured guidance.

One patient from Semporna fasted throughout the month believing he was doing well because he felt no symptoms. Living in a coastal district where access to healthcare may require significant travel, follow up was not always immediate. Like many patients managing diabetes independently during Ramadan, he assumed that feeling normal meant his condition was stable. When his blood tests were eventually reviewed, his blood sugar levels were significantly elevated. Diabetes can behave like a slow rising river. It may appear calm on the surface while dangerous levels build quietly underneath. Without proper monitoring, timely medical review, and structured medical guidance, serious complications can develop silently even when a patient feels well.

Dietary management remains central. Malaysian dietary guidelines encourage balanced meals with controlled carbohydrate portions, adequate fibre and lean protein. During Ramadan, this translates into moderation at iftar and thoughtful planning at sahur. Slow-release carbohydrates such as whole grains may help maintain more stable glucose levels during fasting hours. Adequate hydration between sunset and dawn is essential, particularly in Sabah’s warm climate where dehydration can worsen hyperglycaemia and increase fatigue.

Another misconception persists in many communities where some believe that checking blood glucose invalidates fasting. Religious authorities and medical councils have clarified that finger prick glucose testing does not break the fast. The IDF DAR guidelines explicitly recommend regular self-monitoring during Ramadan, especially mid-morning and late afternoon. Blood glucose below 3.9 mmol/L, which is considered medically low and unsafe, or persistently elevated levels above 16.7 mmol/L with symptoms warrant immediate breaking of the fast for safety.

Kenny Edward Potilu, Assistant Medical Officer and certified Diabetes Educator, Penampang Health Clinic

I spoke to Kenny Edward Potilu, Assistant Medical Officer and Diabetes Educator at Penampang Health Clinic who emphasised that the difference between safe and unsafe fasting often comes down to preparation. “Many patients are still unaware that fasting safely requires proper preparation. We always encourage them to come to the clinic before Ramadan for a pre-fasting assessment. The medical officer will screen their overall condition and determine their risk level. If there are areas that need further guidance, the diabetes educator will provide structured education on meal planning, medication timing, blood glucose monitoring, and when to break the fast. Knowledge is crucial. With proper assessment and education, many moderate-risk patients can fast safely. Without preparation, the risk of complications increases.”

Diabetes management during Ramadan aligns with Malaysia’s National Strategic Plan for Non-Communicable Diseases, which prioritises strengthening primary care, patient education, and continuity of treatment. Ramadan specific counselling should not be seen as seasonal advice but as part of continuous chronic disease management embedded in health clinic services.

There is also a longer-term perspective. For some patients, Ramadan may become a turning point that encourages better portion control, improved medication adherence, and greater health awareness when supported by structured medical guidance. Reduced snacking, increased spiritual reflection, and structured meal timing may reinforce healthier behaviours that extend beyond the fasting month. When approached responsibly, the month can reinforce healthier behaviours that extend beyond Ramadan itself.

For the public, several realities must be understood. Fasting is not obligatory for those whose health is at serious risk. Feeling weak or dizzy is not always a sign of perseverance. It may be hypoglycaemia. Overindulgence at iftar does not compensate for daytime fasting. It may destabilise glucose control for weeks after the month ends.

Ramadan is a month of discipline. For people living with diabetes, discipline must include medical responsibility. When fasting decisions are guided by evidence, supported by Clinical Practice Guidelines, and aligned with religious exemptions where appropriate, the month can remain spiritually meaningful without becoming a preventable medical emergency. Faith and science are not in opposition. In diabetes care, especially in a state like Sabah where the burden is real and visible, they must move together.

Melvin Ebin Bondi is a PhD candidate in Public Health at Universiti Malaysia Sabah. He writes a weekly public health column for The Borneo Post.

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·