ADVERTISE HERE

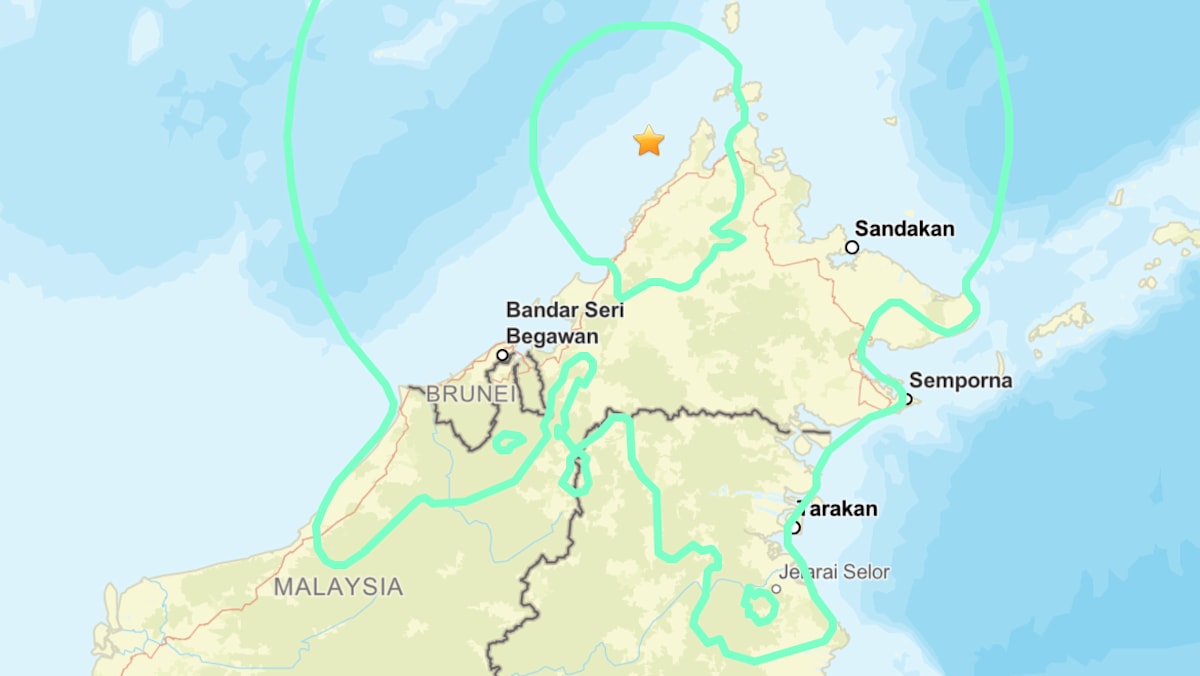

The Malaysia Agreement 1963 carried substantive legal and constitutional weight rather than serving a merely symbolic purpose. – AI generated image

NOT many Malaysians, particularly those in West Malaysia and among the younger generation, possess a truly in-depth understanding of the Malaysia Agreement 1963, commonly known as MA63. In school, the formation of Malaysia often appears as a brief and celebratory milestone.

NOT many Malaysians, particularly those in West Malaysia and among the younger generation, possess a truly in-depth understanding of the Malaysia Agreement 1963, commonly known as MA63. In school, the formation of Malaysia often appears as a brief and celebratory milestone.

Students learn that on 16 September 1963, the Federation of Malaya joined with Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore to form a new nation. Beyond that summary, however, the deeper constitutional negotiations, safeguards and political compromises that shaped the federation rarely receive meaningful attention.

This limited treatment in the national curriculum has had lasting consequences. While students encounter the date and basic structure of Malaysia’s formation, key elements such as the Cobbold Commission, the Inter Governmental Committee Report, and the 20-point and 18-point memoranda from Sabah and Sarawak receive only light mention. As a result, many Malaysians grow up with an incomplete understanding of the way Sabah and Sarawak became part of Malaysia and under which constitutional terms.

The national story frequently presents Sabah and Sarawak as joining an already existing country. In reality, the process carried greater complexity. The formation of Malaysia in 1963 created a new federation grounded in negotiations and agreed safeguards. For leaders in Sabah and Sarawak at the time, this decision represented entry into a partnership rather than surrender of autonomy. That distinction remains crucial for understanding continuing debates about federal and state relations today.

The Malaysia Agreement 1963 carried substantive legal and constitutional weight rather than serving a merely symbolic purpose. It formed a legal and constitutional package that included the Agreement Relating to Malaysia signed in London in July 1963, the Malaysia Act 1963 passed by the United Kingdom and amendments to the Federal Constitution of Malaya providing for the enlarged federation. The negotiations drew upon the findings of the Cobbold Commission, which assessed public opinion in North Borneo and Sarawak, and the work of the Inter Governmental Committee, which detailed constitutional arrangements. Local leaders submitted memoranda outlining their concerns and conditions. In Sabah, this became known as the 20-point memorandum, and in Sarawak, the 18-point memorandum.

These memoranda articulated safeguards in areas such as religion, language, immigration control, financial arrangements, land, native customs and the structure of federal and state relations. The central idea remained clear. Sabah and Sarawak would form Malaysia together with Malaya and Singapore as partners in a new federation rather than as subordinate territories absorbed into an existing state.

One of the visible safeguards that continues today concerns immigration autonomy. Unlike states in Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak retain authority over immigration into their territories. Malaysians from the peninsula require permission to work or reside long term in these states. This power aimed to protect local interests and demographic balance, given the smaller populations of the Borneo territories at the time of formation. Immigration control remains one of the clearer examples of authority reflecting the original understanding of MA63.

Religion presented another sensitive issue. While Islam stood as the religion of the Federation in Malaya, assurances provided that no official state religion would be imposed upon the Borneo territories at the outset and that religious freedom would receive protection. Over time, Islam became the official religion of Sabah, while Sarawak has maintained a more explicitly secular constitutional position. In practice, both states remain pluralistic, with Christianity playing a significant role in society. Many East Malaysians view this religious diversity as part of the spirit of the federal compact.

Language and education also held major importance. English received permission to continue as an official language in Sabah and Sarawak for a transitional period, along with understandings about its use in courts and legislative assemblies. Over the decades, however, federal education policies and national language standardisation reduced much of this distinctiveness. The national curriculum comes under central determination, and although English remains widely used in business and administration, especially in Sarawak, discretion at the state level in education policy remains limited. This gradual centralisation has shaped perceptions regarding the extent to which the spirit of the original agreement continues to receive full respect.

Land and native customary rights stood at the centre of concerns among indigenous communities in both Sabah and Sarawak. Under the federal arrangement, both states retained stronger authority over land matters than states in West Malaysia. Native customary rights remained under state jurisdiction. Constitutionally, these powers largely persist. However, land disputes related to logging, plantation development and infrastructure projects have generated tensions and court cases. These disputes highlight the complex interaction among state authority, federal oversight and the rights of indigenous communities. They also demonstrate that autonomy on paper alone fails to automatically prevent practical conflict.

The issue generating the most sustained debate over the decades concerns natural resources, particularly oil and gas. In 1974, the federal government enacted the Petroleum Development Act, vesting ownership and control of petroleum resources in the national oil company Petronas. Under the prevailing arrangement, oil producing states receive a five per cent cash payment based on the value of petroleum produced. Many in Sabah and Sarawak argue that this arrangement fails to reflect the spirit of MA63, which they believe envisioned greater fiscal autonomy and a more equitable share of resource wealth.

In recent years, Sarawak has asserted its position more strongly by establishing its own state oil and gas entity and imposing sales taxes on petroleum products. Negotiations between the state and the federal government have produced increased revenues and certain recognitions of state rights, although Petronas continues to play a central role in national energy policy. Sabah has similarly pursued higher royalties and greater participation in resource management, achieving incremental gains rather than fundamental restructuring. For many East Malaysians, resource control represents more than an economic concern. It reflects the broader question of whether the principle of partnership in MA63 continues to receive proper recognition.

Constitutional amendments have also shaped public perception. In 1976, amendments altered provisions relating to the status of Sabah and Sarawak within the federation. Critics argue that these changes symbolically reduced the sense of equal partnership and signalled a shift toward stronger central authority. Legal scholars continue to debate the precise implications, yet the political symbolism has left a lasting impact on public sentiment in East Malaysia.

Over time, administrative centralisation in areas such as education, health care, infrastructure planning and development funding has reinforced concerns about imbalance. Federal agencies manage significant portions of development expenditure in Sabah and Sarawak. Although such arrangements remain common in federations, they can create a perception that state governments function with financial dependence and limited flexibility in shaping development priorities.

Despite their natural resources, Sabah and Sarawak continue to face infrastructure gaps, rural poverty and geographic challenges requiring substantial funding. Both states rely heavily on federal allocations to address these needs. This economic reality influences negotiation dynamics between state and federal governments. Greater autonomy often requires financial independence and administrative capacity, both of which demand time to strengthen.

The question of whether MA63 has been fulfilled requires a nuanced and complex answer. In some respects, the constitutional framework still recognises special rights and powers for Sabah and Sarawak. Immigration autonomy, land jurisdiction and aspects of native law remain distinctive features of the federation. In other respects, federal legislation, constitutional amendments and administrative practice have centralised authority in ways that many believe depart from the original understanding of MA63.

Several factors help explain this complexity. One factor involves ambiguity within historical negotiations. Not every expectation articulated in the 20-point and 18-point memoranda entered binding constitutional provisions word for word. Over time, differing interpretations have emerged regarding which elements received legal entrenchment and which reflected political aspiration. Another factor concerns the amendable nature of the Federal Constitution. Parliament holds the power to amend it, and governments with strong majorities have reshaped aspects of federal and state relations. Reversal of earlier amendments requires broad political consensus, which often proves difficult to secure.

Political considerations also shape the way federal and state relations evolve. Federal leaders often exercise caution when asked to transfer greater fiscal or policy authority to the states, especially if such transfers could weaken central coordination, national planning or political influence. At the same time, state leaders frequently choose negotiation and step by step bargaining over direct legal confrontation, believing that gradual concessions stand a better chance of success than court battles. The ability of a state government to manage additional responsibilities also matters. Greater autonomy requires strong administrative systems, skilled personnel and sound financial management, all of which take time and resources to develop.

Why should this matter to Malaysians beyond Sabah and Sarawak? The answer lies in the nature of the federation itself. MA63 serves as a foundational agreement shaping the country’s constitutional identity rather than merely a regional document. A fuller understanding of its history strengthens national unity by grounding it in mutual respect and shared knowledge.

When Malaysians in the peninsula appreciate that Sabah and Sarawak entered the federation through negotiated safeguards, discussions about autonomy, revenue sharing and development become more informed and less emotional. Recognition of the historical context allows more constructive dialogue about federalism, equality and partnership.

For younger Malaysians especially, deeper study of MA63 would foster a more nuanced understanding of the country. Such learning would demonstrate that unity and uniformity are distinct concepts, and that diversity within a federation can be given constitutional structure. It would also encourage critical thinking about the way constitutional arrangements evolve over time.

Calls from leaders, academics and civil society groups in Sabah and Sarawak to enhance public understanding of MA63 represent efforts to strengthen national understanding rather than attempts to divide the nation. These calls seek completion of the national story. Improved history education should include clearer explanations of the agreement, its key provisions and the context of its negotiation. Students should encounter primary documents and engage in discussion about the way historical safeguards continue to influence contemporary issues.

Malaysia’s future depends on a shared and accurate understanding of its past. A federation as diverse as Malaysia relies on constitutional literacy, historical honesty and mutual respect rather than simplified narratives alone. More than six decades after its signing, the Malaysia Agreement 1963 remains a cornerstone of the nation. It deserves recognition as the constitutional foundation upon which Sabah, Sarawak and Malaya agreed to build a common future. Only through full understanding of MA63 across regions and generations will Malaysians meaningfully shape the federation it created.

Dr Richard A. Gontusan is a Human Resource Skills Training and Investment Consultant. Much of the information in this article was sourced from the public domain. His views expressed in this article are not necessarily the views of The Borneo Post.

1 hour ago

8

1 hour ago

8

English (US) ·

English (US) ·